Pep Guardiola wanted to be Sergio Busquets: "If I could come back and play as any player, it would be Sergio Busquets."

Lionel Messi used Busquets as a life preserver: "When there will be trouble, he will be there."

Johan Cruyff thought he was automatic: "He is the kind of player you don't need to explain anything to. You just put him in his position, and he performs."

To Vicente del Bosque, Busquets was, well, soccer: "If you watch the whole game, you won't see Busquets -- but watch Busquets, and you will see the whole game."

And to Xavi Hernandez, his former teammate and coach: "Sergio Busquets is the smartest player I've ever seen or played with: he's a genius." Xavi then also said: "We must sign a pivot this summer. It's a priority to have new player there following Busquets' exit."

With Busquets departing Barcelona this summer after spending his entire career in Catalonia, the club needs only to find another guy who the best coach in the world wanted to be and the best player in the world trusted with his life. Someone who Cruyff, the most influential mind in modern soccer, saw as a distillation of the sport itself, a player so elemental to the functioning of the teams he played in that his coaches and teammates were almost incapable of speaking about him in human terms.

That's all then, huh? Does that player even exist?

What was Busquets?

There is an entire chapter in my book, "Net Gains: Inside the Beautiful Game's Analytics Revolution," devoted to the mystery of Busquets. What made his teammates revere him in a near-spiritual sense, what made his managers worship him, what made him a litmus test for whether or not you knew ball?

The beauty of Busquets, in particular, is that numbers can't really come close to quantifying the impact he had. While that perhaps suggests his impact wasn't quite as monumental as everyone says -- pardon the heresy for a second, but would Barcelona really have been that much worse with Michael Carrick playing the same position? -- I don't think the aggregate number-counting of on-ball actions can come close to comprehending the way Busquets influenced the game.

To me, Busquets shifted the geometry of the sport in a way that no player ever has. For everyone else, soccer was mostly an up-and-down game, with goals at both ends. For Busquets, the field was an always-moving 360 degrees. It was a record spinning with him at the center and everyone else whipping around him, moving faster and faster, the further you got away.

You could only really come close to quantifying Busquets if you had, say, high-speed cameras planted all around the stadium taking hundreds or thousands of pictures every second. And for one LaLiga match in 2017, Luke Bornn and Javier Fernandez had this.

Bornn is a founder of the analytics company Zelus Analytics, and also part of the ownership groups for Toulouse FC and AC Milan. Fernandez used to work for Barcelona and is now with Zelus, too. For their paper "Wide Open Spaces: A statistical technique for measuring space creation in professional soccer," they were able to measure how Barcelona players both created and occupied space over the course of a match against Villarreal.

While the headline finding was that Messi walks better than everyone -- he slows down once he's in "high-value" space -- they also discovered, or reaffirmed, the following: "Busquets shows an incredible collaborative behaviour by generating space almost anywhere around the field." While most other players on the team had specific tendencies or relationships across the field, Busquets received and created space for almost all of his teammates. Watch Busquets and you do see the whole game.

However, that's not to say that Busquets didn't do a ton of the things that show up in simpler on-ball data, either. Let's take the 2015-16 season as an example. Barcelona won LaLiga for the second year running and Busquets played the most league minutes of his career (2,899) up to that point. He was 27 at the beginning of the season; this was his peak.

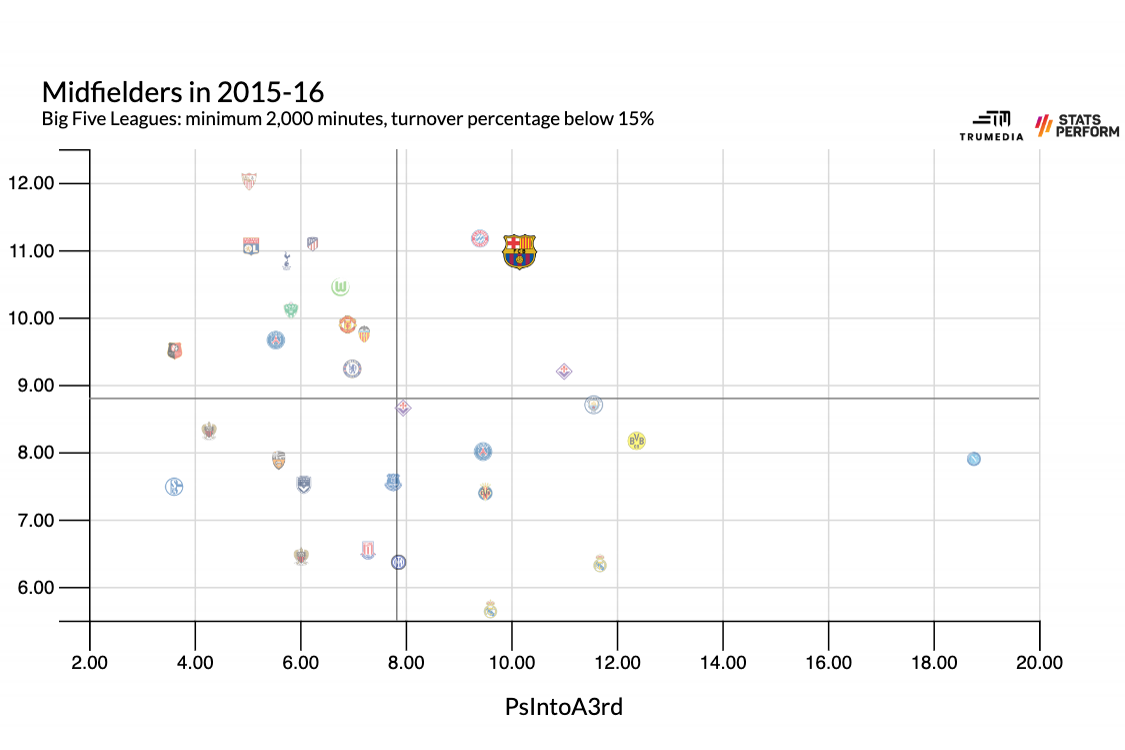

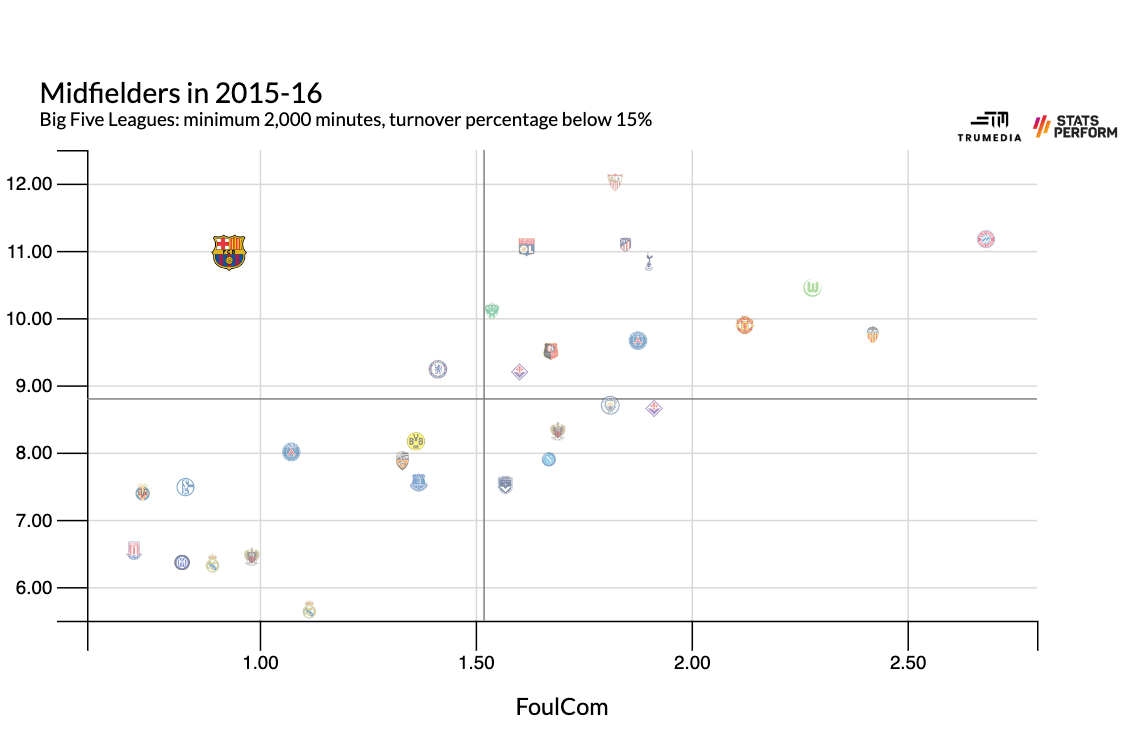

Broadly, Busquets was a player who constantly won back possession, was always on the ball and never lost it, but also always knew when to push play forward. In 2015-16, there were 30 midfielders across Europe who played at least 2,000 minutes and turned the ball over less than 15% of the time. Here's how they compare by combined tackles and interceptions (adjusted per 1,000 opponent touches) and passes played into the attacking third:

At the top, you've got Sevilla's Grzegorz Krychowiak, who won the ball nonstop but rarely played it forward. And at the outer-right reaches, you've got Napoli's Jorginho, who did the opposite. And then in the upper-right quadrant, it's only Busquets and Arturo Vidal, who was lights-out under Guardiola at Bayern Munich, but also committed more fouls (2.68) than any of the other 30 midfielders on the list. Busquets, meanwhile, committed just 0.93 fouls per 90 minutes.

That, too, made him an outlier. There's a pretty strong relationship with how often you win the ball and how often you commit fouls -- unless you're Sergio Busquets.

Busquets combined quantity with quality on -- and off -- the ball better than any modern midfielder ever has.

Who is the next Busquets?

If you ask Busquets, he'll tell you it's the guy who's playing the Busquets role for his old coach: Manchester City's Rodri. And per analysis by the analytics company StatsBomb, Rodri was the most similar under-26 player to Busquets in Europe this past season:

The most similar under-26 player to Sergio Busquets in 2022/23?

— StatsBomb (@StatsBomb) June 14, 2023

Rodri of Manchester City. Florentino Luís of Benfica was another close match#SimilarPlayers pic.twitter.com/urpWUrcdFN

A similar analysis by the consultancy Twenty First Group found the same thing:

Who could replace S. Busquets at @FCBarcelona ? https://t.co/Sho1Z55Dtb pic.twitter.com/k4YMIIf2lS

— Aurel Nazmiu (@AurelNz) June 8, 2023

Of course, style and system play a role in all of this. Is it surprising that the player playing the same position as Busquets for the coach who gave Busquets his professional debut produces a similar statistical output? And although the Twenty First Group model identifies Declan Rice as similar to Busquets too, well, you've watched Declan Rice play, haven't you? They're not similar players at all. The latter is way more physical, much more of a ball carrier than a small-space problem solver.

Using tracking data, the company SkillCorner analyzed the kinds of passing-options that were available to Busquets and Rice when they had the ball this past season. Most of Rice's options were to uncongested, less dangerous wide areas, while Busquets frequently had to make more difficult, more vertical passes:

This allows you to understand the context a player operates in and establish a passing profile for scouting prospects:

— SkillCorner (@SkillCorner) May 11, 2023

➡️ Busquets gets Ahead and In-Behind runs to execute Barca's fast transition style

➡️ Declan Rice's opportunities provided through Wide and Coming Short Runs pic.twitter.com/IS8y5sTYkw

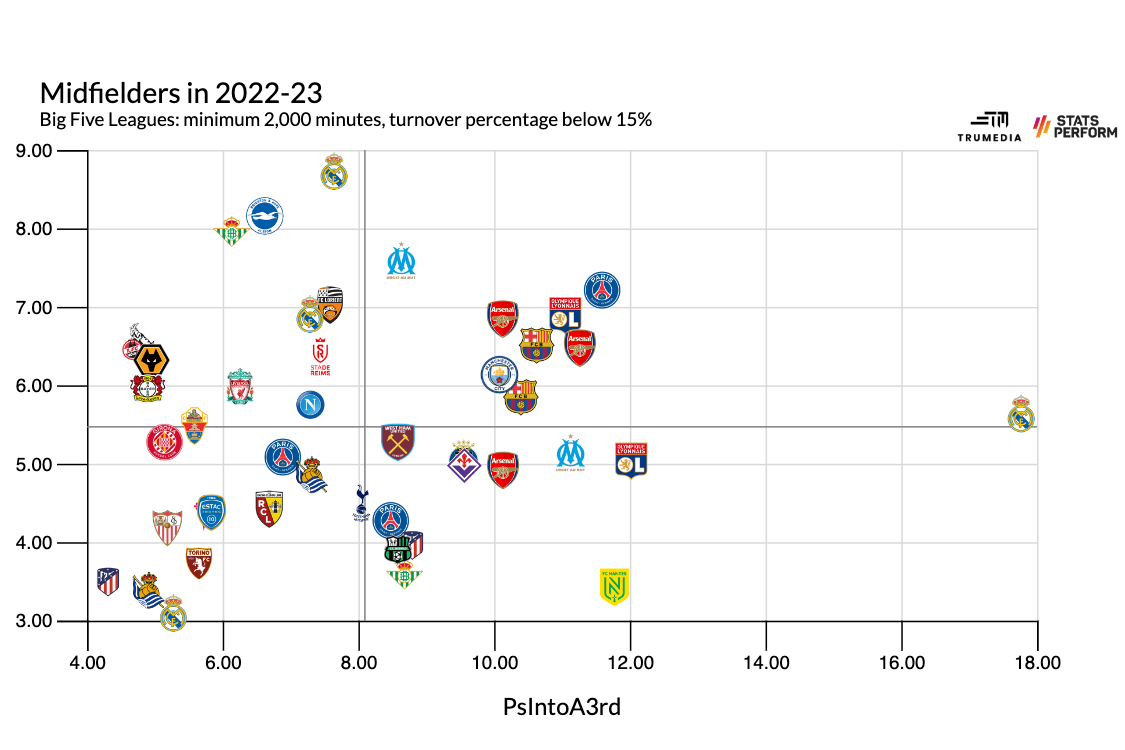

The other problem with all of this: we're comparing these players to Sergio Busquets this season. You don't want to sign the physically limited, 34-year-old Sergio Busquets; you want the guy from 2015-16. Here's the same chart from above, but for the past season:

The influence of Busquets and Guardiola is evident in how many more names are now in that top right quadrant. Still there, though, is Busquets himself.

The two Arsenal players are Thomas Partey and Jorginho, neither of whom should be options for Barcelona for a variety of reasons. The PSG player is Marco Verratti, who is very much a "Barcelona" player -- and has been a target in the past -- but is only four years younger than Busquets. The Lyon player is Thiago Mendes, who is a year older than Verratti. The only two prime-age players in the cluster are the aforementioned Rodri and Busquets' club teammate Frenkie de Jong, who has shown himself incapable of playing as Barcelona's deepest midfielder.

The answer, instead, might be found by looking in the opposite direction, in more ways than one. All the way to the right is Real Madrid's Toni Kroos, and all the way to the top is his teammate Aurelien Tchouameni. Rather than leaning on any one player the way Barcelona did with Busquets, Madrid has divided those responsibilities up among multiple players.

There could be a lesson in there for Barcelona as they approach their midfield rebuild this summer. If you try to replace Sergio Busquets directly with a similar kind of player, you're guaranteeing you're going to get someone worse. No one will ever be better at being Sergio Busquets than Sergio Busquets.