Every weekend, we're given access to millions of publicly available data points from each game across each major soccer league across the world. Want to know how many final-third tackles Monza made against Torino in Serie A? Curious about Toulouse star Branco van den Boomen's chance creation against Lyon? Interested in how effective Brenden Aaronson's dribbling was for Leeds United away to Nottingham Forest?

It's all out there, and it's all not enough.

The idea -- how we both have too much data and way too little -- is a big reason why I wrote my book, "Net Gains: Inside the Beautiful Game's Revolution." We know more about soccer than ever before, but that's also making it clear how little we actually know about how the game works. All these numbers record everything that happens with the ball, but so few of the numbers actually tell us what's helping teams win games.

This problem was the premise of a famous New York Times Magazine story, "The No Stats All-Star," written by Michael Lewis in 2009 about Houston Rockets forward Shane Battier. Despite not scoring many points, grabbing lots of rebounds or creating any assists, Battier seemingly made the Rockets play better simply by being on the court. Meanwhile, it was announced last week that soccer's version of Battier [and the subject of his own chapter in "Net Gains"] the subtle midfield genius Sergio Busquets, would be leaving Barcelona after 15 seasons with the club.

With that in mind, can we find some unsung Premier League players from this season who might be doing more than these standard on-ball numbers suggest to help their teams win?

The defender who doesn't defend

Measuring defense is an issue in every sport, including baseball, the most quantified and most optimized major game. Early on with the Oakland Athletics, "Moneyball" general manager Billy Beane didn't value defense because there wasn't an easy way to measure it. Over time, baseball teams have improved their valuations of defensive performance and started to find undervalued players by focusing on areas like pitch-framing, the simple act of a catcher manipulating his glove to fool an umpire into thinking a pitch that was a ball was actually a strike. Players previously thought to be league-average-or-worse were suddenly worth multiple wins and millions of extra dollars.

Despite that, some of the metrics used to evaluate defense will drastically change from year to year for a given player. It's unlikely that these players suddenly got worse at playing defense, and it speaks to the core problem of measuring it across all sports: it's reactive.

When you're attacking, you have the ball and you get to decide what you're going to do with it. The defense can organize itself in a way to try to prevent you from doing something, or prevent you from even trying to do something. But ultimately, the team with the ball makes a decision and then forces the defense to act against that decision.

So, when you're trying to record defensive statistics, you're -- in many ways -- recording an echo of the offense that team and that player played against. A center-back will make more tackles when more players attempt to dribble past him. They'll win more aerial duels against a team that crosses the ball more, or against a smaller striker, or against a team that are dominating possession. More broadly, I've heard it described among analytics folks in the NFL that the best predictor of teamwide defensive performance is ... the quality of offenses they play against.

The two best defenses in the Premier League this season don't really have that issue; the schedule is the same for everyone in soccer. One of the teams is obvious: Manchester City, who are the best defensive team in the league nearly every season. The other might be obvious now, too, but that wasn't the case 12 months ago, when they finished in 11th place.

Last year, Newcastle United conceded 62 goals in the Premier League. This year, they've halved that number with three games to go: 31, tied with City for fewest in England. What changed from year to year?

Well, they signed a defender for €37 million who doesn't really do anything. Among Premier League center-backs, here's where Sven Botman ranks (in percentile) across a number of defensive metrics:

- Tackles: 36th

- Interceptions: 30th

- Blocks: 53rd

- Clearances: 36th

- Aerial duels won: 55th

Sure, you say, but he's playing for a better team that has more of the ball. Aren't center-backs from top-four teams supposed to contribute more with the ball than without it?

Good try! He also ranks only in the 26th percentile for progressive passes and carries among his position. Oh, and he's scored zero goals so far this season.

But aren't center-backs on top teams simply asked to do less without the ball since their teams have more of it? Wouldn't Botman's defensive numbers suffer because of it?

Allow me to present to you the same numbers for Botman's central defensive partner, Fabian Schar:

- Tackles: 41st

- Interceptions: 74th

- Blocks: 20th

- Clearances: 51st

- Aerial duels won: 88th

- Progressive passes: 74th

- Progressive carries: 66th

Schar is way more active both without and with the ball. And yet, Schar was seemingly a middling defender for a relegation-quality team in the four years prior to Botman's arrival. The other big arrivals after the Saudi-backed takeover, as well as manager Eddie Howe, have surely had a massive effect, but in the 23 games under Howe last season, Newcastle allowed four more goals than they've done in 35 games this season.

The biggest defensive difference between those splits is the presence of Botman, who arrived from Lille over the summer. His steadying presence allows Schar to be more active and, rather than making lots of plays, Botman only gets involved when needed. Like any great center-back, his positioning also prevents him from being in places where he needs to even make an interception or a tackle in the first place. Computers can't pick up on it yet, but Botman's defensive impact this season has been undeniable.

The midfielder who doesn't pass

The farther you move up the field, the harder it gets to influence a game without leaving any kind of statistical record. Busquets himself did a ton of stuff that showed up in the numbers:

With Busquets, I was more intrigued by how all of that data contributed to winning; how important was he to Barcelona's success when compared to Xavi and Andres Iniesta, or Lionel Messi, David Villa and Luis Suarez?

The canonical example of a midfielder who didn't do a lot but seemed to contribute a lot to winning was Liverpool's Georginio Wijnaldum. He played nearly 3,000 minutes for a team that won the title with 99 points in 2019-20, but he didn't rate above the 12th percentile for tackles and interceptions among midfielders. He was in the 58th percentile for passes attempted and the 40th percentile for progressive passes completed.

For context, the five most statistically similar midfielders in the Premier League that season, per the algorithm from the site FBref, were Tottenham Hotspur's Moussa Sissoko, Burnley's Jeff Hendrick, Everton's Tom Davies, Aston Villa's Douglas Luiz and Bournemouth's Junior Stanislas. And yet, despite a meager statistical output, Wijnaldum was able to play 86% of the minutes for a team that won 26 of their first 27 league games.

It's hard to find anyone else like Wijnaldum, simply because midfield is a game of volume. No single action is particularly valuable in the midfield -- so far from goal -- and so it's more about racking up a high number of low-value actions that add up over time. Real Madrid's Toni Kroos is a world-class player not because he makes one great pass per game; he's a world-class player because he makes 15 of them. If you're not doing that, then you're likely on a bad team (in part because you're not helping!) or you're on a good team and you're not getting any playing time.

Instead, let's highlight a midfielder who simply doesn't do the thing that all midfielders are expected to do: pass. If you picture your ideal version of a midfielder, you're picturing someone like Busquets -- a player who's as comfortable controlling a ball with his feet as he is with his hands. Picture the opposite of that ... and you've got Thomas Soucek.

The 6-foot-3 Czech midfielder has attempted 31.2 passes per game this season; the league-leading midfielder, Rodri, is all the way up at 92.5. Soucek has completed 71.4% of those passes, compared, again, to league-leading Rodri at 91.1%. But it's not like that low efficiency is getting any payoff from some higher-risk completions, either. He's only in the 14th percentile for progressive passes completed: 2.9, with Chelsea's Enzo Fernandez leading the league on 9.5.

Instead, Soucek is like a MLB home-run hitter who is all walks, dingers, and strikeouts. Rather than messing around with this low value-stuff, he only spends his time doing the obviously important things, popping up in both penalty areas. He's in the 94th and 99th percentile, respectively, for clearances and aerial duels won among midfielders -- meaning he's constantly putting an end to high-value attacks from opponents. And in possession, since he's barely touching the ball, he's making sure he's touching it in the most dangerous area on the field: Soucek is in the 65th percentile among midfielders for penalty-area touches and the 67th percentile for non-penalty expected goals.

The latter two aspects have started to decline, perhaps as Soucek ages deeper into his late 20s, and that might help explain West Ham's struggles this season. But in his four years in London, Soucek has provided an aspirational form for workers across the planet: He's maximized his impact while minimizing his involvement.

The forward who doesn't score

Controversial opinion alert: Kai Havertz is a really good player!

It's just that he doesn't do the one thing everyone expects players in his role to do: put the ball into the back of the net. He's basically the inverse of the Soucek of center-forwards -- now there's a sentence for you -- in that he does all of the little things but not the one big thing.

In possession: He never loses the ball. He receives a ton of progressive passes. He plays a ton of progressive passes. He carries the ball forward a bunch. He creates chances for his teammates.

Out of possession: He's a fantastic presser, so he's constantly helping to gain back possession on the ground. Oh, and he's 6-foot-1, so he's constantly winning balls in the air and frequently making clearances from Chelsea's own box.

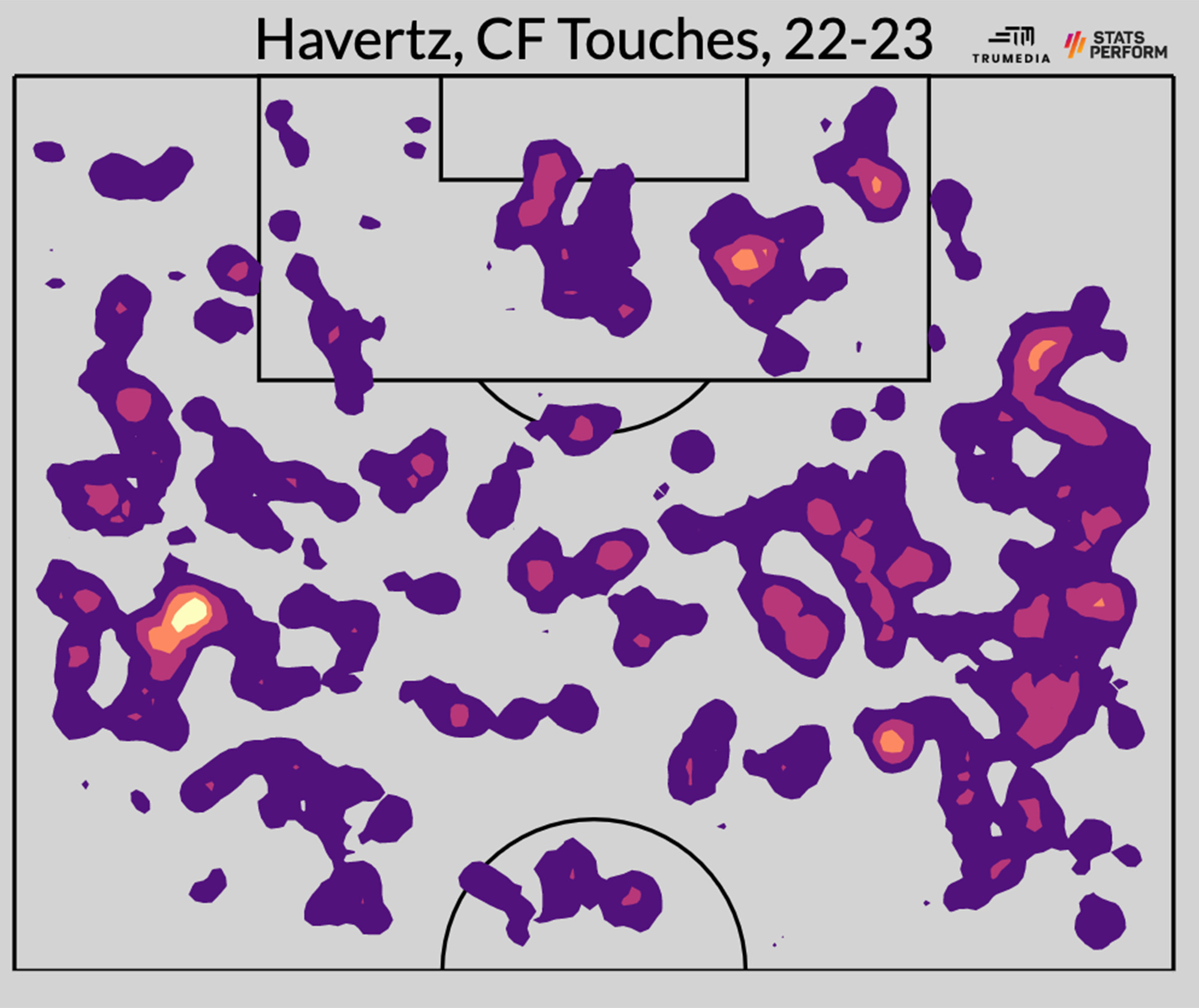

When playing as a center-forward this season, he's drifted all across the field, rather than staying fixed centrally:

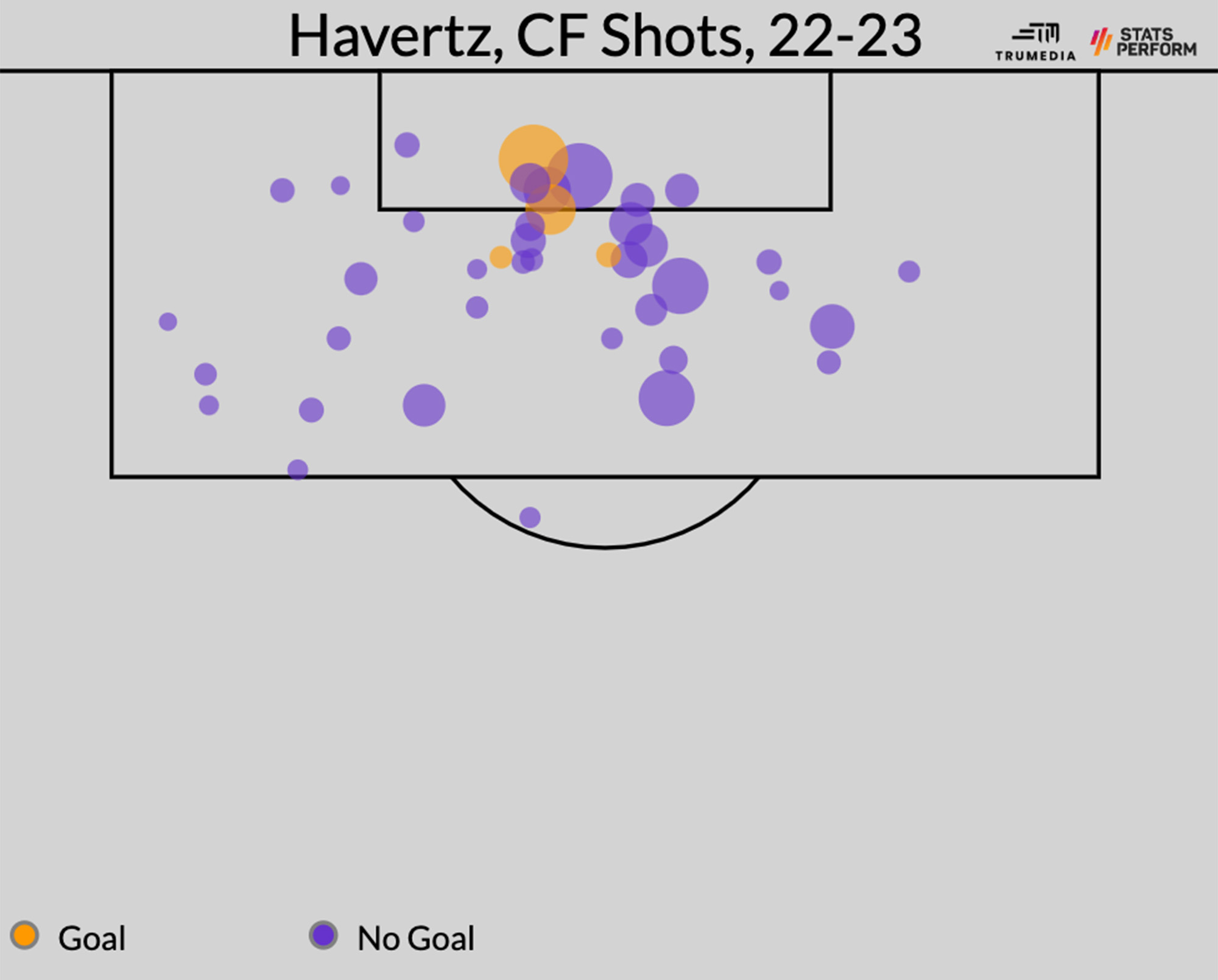

But despite being involved so much outside the box, he hasn't wasted possession with bad shots from long range:

Havertz has never scored more than eight goals in a Premier League season, and he's only averaged 2.4 shots per 90 minutes with Chelsea in his three years with the club. That's basically a 50th-percentile mark among Premier League forwards, which is an even smaller number than it seems given that he plays for one of the richest teams in the league.

The 23-year-old is the kind of player who does all the little things that help a team win, but when the team isn't winning, the focus shifts to the main thing he doesn't do.

Chelsea won the Champions League in 2021, and they then were one of the best teams in Europe last season -- both with Havertz playing center-forward. He's not going to terminate defenses on his own like Manchester City's Erling Haaland, but compared to everyone on Chelsea's roster in this nightmare season, Havertz seems like one of the few players playing at the same level as he did in seasons past. He is what he is; it's not his fault he's currently the club's leading scorer.